Greetings, friends! Welcome to etutorguru. Within this piece of writing, we have furnished CBSE Notes for Class 10 History Chapter 2, “Nationalism in India,” accompanied by a mind map. And NCERT solutions Using these resources can help students perform better in exams.

What You’ll Find In This Post –

- Animated Video: Nationalism in India

- 1. The First World War, Khilafat, and Non-Cooperation : Nationalism in India

- 1.1 The Idea of Satyagraha : Nationalism in India

- 1.2 The Rowlatt Act : Nationalism in India

- 1.3 Why Non-cooperation? : Nationalism in India

- 2. Differing Strands within the Movement : Nationalism in India

- 2.1 The Movement in the Towns : Nationalism in India

- 2.2 Rebellion in the Countryside : Nationalism in India

- 2.3 Swaraj in the Plantations : Nationalism in India

- 3. Towards Civil Disobedience : Nationalism in India

- 3.1 The Salt March and the Civil Disobedience Movement : Nationalism in India

- 3.2 How Participants saw the Movement : Nationalism in India

- 3.3 The Limits of Civil Disobedience : Nationalism in India

- 4. The Sense of Collective Belonging : Nationalism in India

- 5. Conclusion : Nationalism in India

- 6. Download PDF Notes : Nationalism in India

- 7. Download MindMap : Nationalism in India

- 8. NCERT Solutions : Nationalism in India

Nationalism in India Class 10 History Chapter 2 CBSE NCERT Notes

Colonial authority led to the revival of nationalist sentiment in India, allowing the British East India Company to gain influence.People developed an anti-colonial sentiment, which was exploited by the Indian National Congress to unify against colonial rule.

Animated Video: Nationalism in India

1. The First World War, Khilafat, and Non-Cooperation

- People were angry and hateful because of the First World War and what it did to them.

- As the war went on, men from villages were forced to leave their homes to fight.

- In 1918-19 and 1920-21, many people in India died of hunger because crops failed in different parts of the country.

- During the war, India was hit by a flu epidemic.

- India had famines and epidemics that killed between 12 and 13 million people.

1.1 The Idea of Satyagraha : Nationalism in India

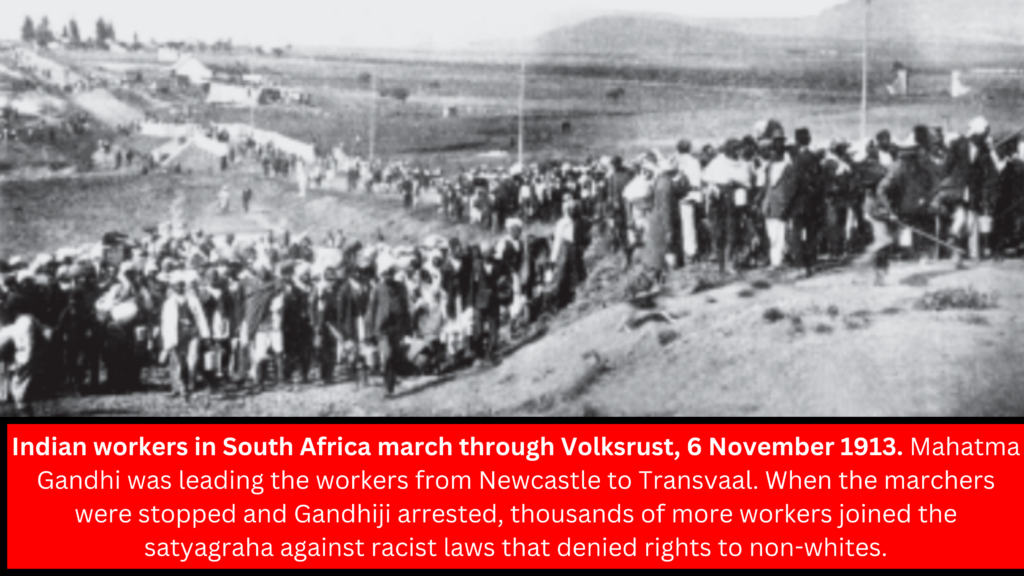

Satyagraha was the idea of truth overcoming all obstructions, which inspired Mahatma Gandhi to unify India against British oppression.

- Mahatma Gandhi organised numerous satyagraha movements throughout India. Champaran in Bihar in 1917 – against the plantation system.

- In 1917, the Kheda district of Gujarat supported peasants who were badly affected by crop failure and plague and thus demanded tax relief.

- Ahmedabad in 1918 – supported cotton mill workers.

1.2 The Rowlatt Act : Nationalism in India

- The Rowlatt Act was passed in 1919.

- The Act gave the government the power to stop political activities and put political prisoners in jail for two years without charges

- On April 6, Mahatma Gandhi started a movement of disobedience to the government.

- Because of this, peaceful marches were stopped and attacked, leaders were put in jail, and Mahatma Gandhi was not allowed to go to Delhi.

- The event at Jallianwalla Bagh happened on April 13.

According to Dyer, the goal of such a cruel act was to “produce a moral effect,” or to instil fear in the people.

- As word of the incident spread, people began to revolt violently.

- There were soon clashes with the police.

- People were mistreated, they were treated horribly – forcing them to rub their nose on the ground, do salaam to the officers, crawl on the streets, etc.

- When he saw the spread of violence, Mahatma Gandhi called a halt to the movement.

The Khilafat Movement : Nationalism in India

- The Ottoman emperor’s power was threatened with the end of World War I and the collapse of Ottoman Turkey.

- To protect the Ottoman emperor’s position and power as the spiritual head of the Islamic World, a Khilafat Committee was formed in Bombay in 1919.

- Mahatma Gandhi raised the issue for his support by two young brothers and leaders, Mohammed Ali and Shaukat Ali, so that the greatest number of people could support it.

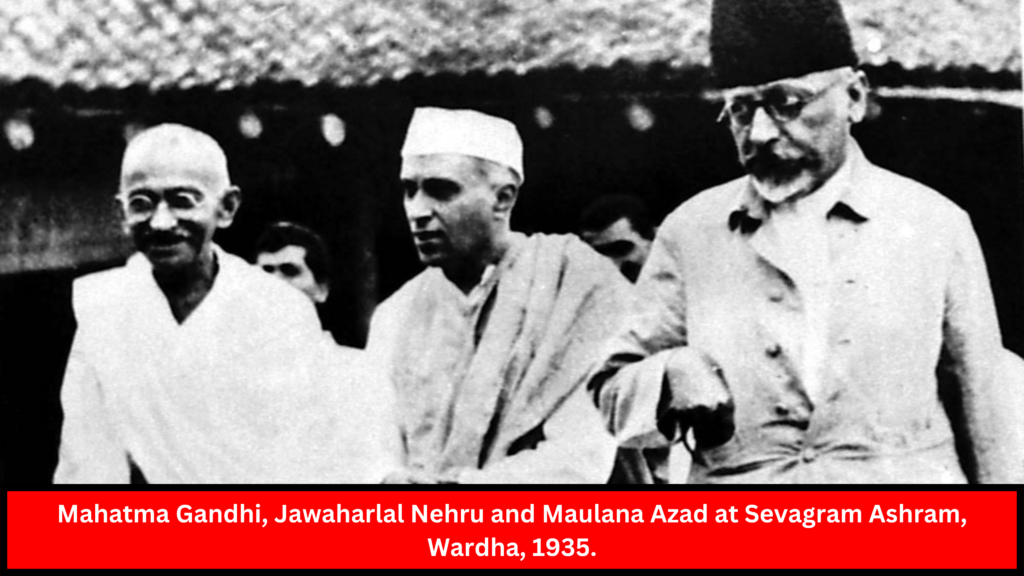

- Sensing a chance to unite Hindus and Muslims, Mahatma Gandhi persuaded Indian National Congress members in Calcutta in September 1920 to embrace the Khilafat issue and promote swaraj.

1.3 Why Non-cooperation? : Nationalism in India

- Mahatma Gandhi believed that British rule in India lasted for many years due to Indian cooperation.

- If the Indians refuse to cooperate, the East India Company will find it difficult to assert its authority.

- The movement was supposed to happen in stages.

- First, Gandhi urged people to reject official titles and boycott civil services, courts, legislative councils, police, and other institutions.

- If the government used force, Gandhiji predicted that the people would launch a full-fledged civil disobedience movement.

- Mahatma Gandhi and Shaukat Ali organised various rallies to spread their message to a wide audience.

- Some Congress members were torn between supporting the Non Cooperation campaign and voting in the approaching provincial elections.

- The members believed that securing seats on the decision-making body would give them some influence over issues concerning the welfare of the people.

- Finally, in December 1920, during the Congress Session in Nagpur, all members resolved to support the Non-Cooperation campaign.

2. Differing Strands within the Movement

2.1 The Movement in the Towns : Nationalism in India

- The movement began in the towns.

- Provincial elections were also boycotted in several areas, with the exception of Madras.

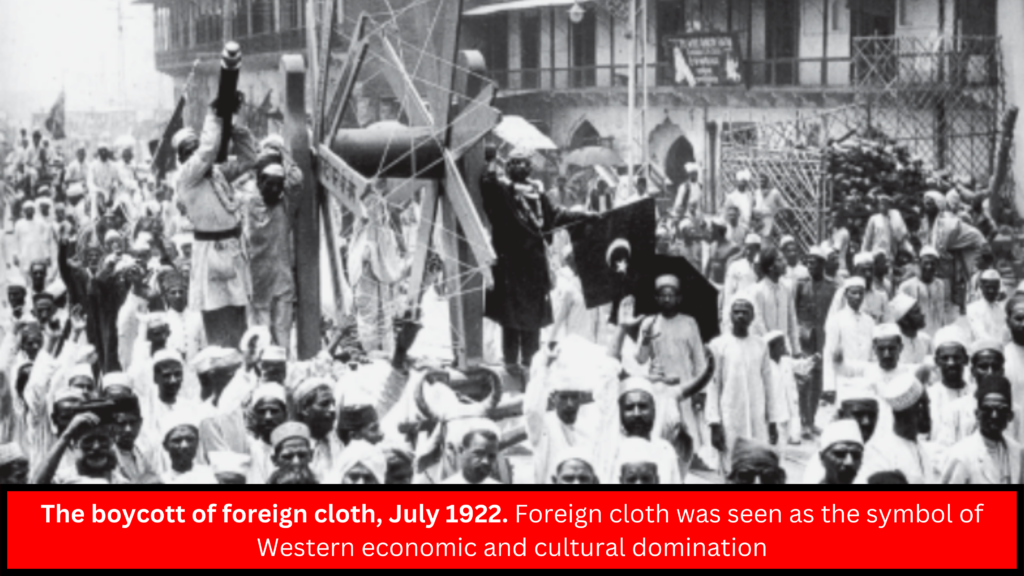

- The boycott of foreign goods was also a result of the non-cooperation movement.

- This resulted in a decrease in the import of foreign-made items.

- People stopped trading in foreign goods, and the popularity of Indian-made clothing and goods grew.

However, this movement had limitations.

- As the non-cooperation movement grew, more and more people started to wear things that were made in India.

- But Khaki was more expensive than foreign goods made by machines, so poor people couldn’t buy it.

- Also, as students and government workers stopped going to schools and offices run by the government, there were not many other options.

- Because schools and offices took so long to open, students and people started going back to them after a while.

2.2 Rebellion in the Countryside : Nationalism in India

Peasants of Awadh : Nationalism in India

Peasants in Awadh were in a dire situation prior to the start of the Non Cooperation movement. Their rage and hatred were directed at their landlords, who forced them to do begar (unpaid labour) and extracted high rents and other taxes.

- Peasant movements occurred in several parts of the region.

- They wanted the beggar to be abolished and rents to be reduced.

- They also planned nai-dhobi bandhs for it.

- They did this by depriving landlords of the services of barbers and washermen.

- Jawaharlal Nehru visited these areas at the time, and after listening to their concerns, the Oudh Kisan Sabha was formed, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and Baba Ramchandra.

- When the noncooperation movement began, the issues of the peasants were also highlighted, and the peasants actively engaged in the movement.

- Congress tried to include peasants in the battle because they were in huge numbers and also provided food for the society.

Gandhi’s supporters attempted to incite peasants to violence by attacking the landlord’s house, food grain storehouses, and bazaars.

Tribal peasants : Nationalism in India

- The tribals of Andhra Pradesh’s Gudem Hills were misled in the name of swaraj.

- The tribals were victims of the colonial government’s cruelty.

- The government had prohibited livestock grazing and entering forest areas.

- Not only was the people’s way of life at stake, but they also believed that their traditional rights were being eroded.

- This infuriated the tribals.

Around this time, a leader named Alluri Sitaram Raju appeared among them.

- He said he had supernatural abilities, like being able to make accurate astrological predictions and being able to take bullets.

- People began to follow him because he gave them ideas.

- Raju spread Mahatma Gandhi’s message of not working with the government by telling people to wear khaki and not drink alcohol.

- He told the people that they couldn’t use nonviolence to get their land back; instead, they would have to use violence.

- Raju was caught and killed in 1924. Because of this, he became a folk hero.

2.3 Swaraj in the Plantations : Nationalism in India

- Assamese plantation workers had their own interpretation of swaraj.

- Plantation workers were not permitted to emigrate under the Inland Emigration Act of 1859.

- Everyone had a different interpretation of what swaraj meant.

- Regardless of their views on swaraj, they all desired a nation free of the colonial government.

- Everyone wanted the miseries inflicted on them directly or indirectly by the Company government to end.

3. Towards Civil Disobedience : Nationalism in India

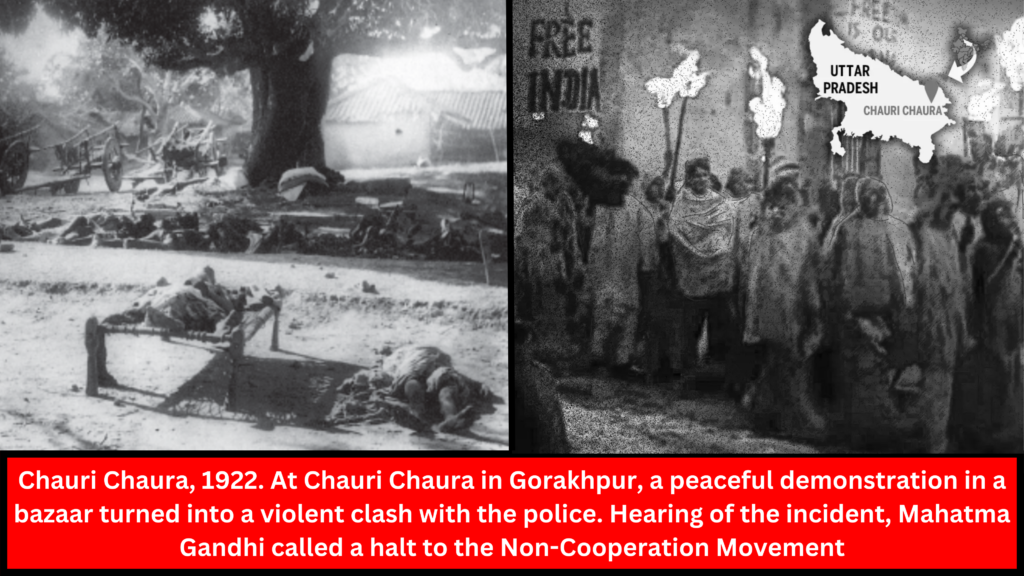

- In February 1922, Gandhiji called an end to the Non-Cooperation movement.

Gandhiji believed that people needed to be properly trained for peaceful mass struggles. - Meanwhile, an internal discussion within the Congress party erupted.

- Some members were hesitant to announce the approaching elections.

- This internal debate resulted in the foundation of The Swaraj Party within the Congress, led by C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru.

The younger members, such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, desired total independence from British rule.

- The economic depression, leading to agricultural prices from 1926 and complete collapse till 1930, left farmers and peasants in complete devastation.

- Along with it, a commission under Sir John Simon was constructed by the Tory government in Britain.

- The commission was set up to regulate the functioning of the constitutional system in India against the nationalist movement.

- The Simon Commission was met with the slogan “Go back, Simon” in 1928.

- To calm the uprising Under Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership, the Lahore Congress officially declared the democratic revolution in December 1929.

3.1 The Salt March and the Civil Disobedience Movement : Nationalism in India

Everyone worshipped salt as a deity. Gandhiji used the Britishers’ monopoly over its production and salt tax to spread his swaraj message. On January 31, 1930, Mahatma Gandhi issued 11 demands in a letter to Viceroy Irwin. The requests came from all segments of society. He made certain that the demands were broad enough to encompass as many people as possible. One of the demands was to abolish taxation. Gandhiji stated in the letter

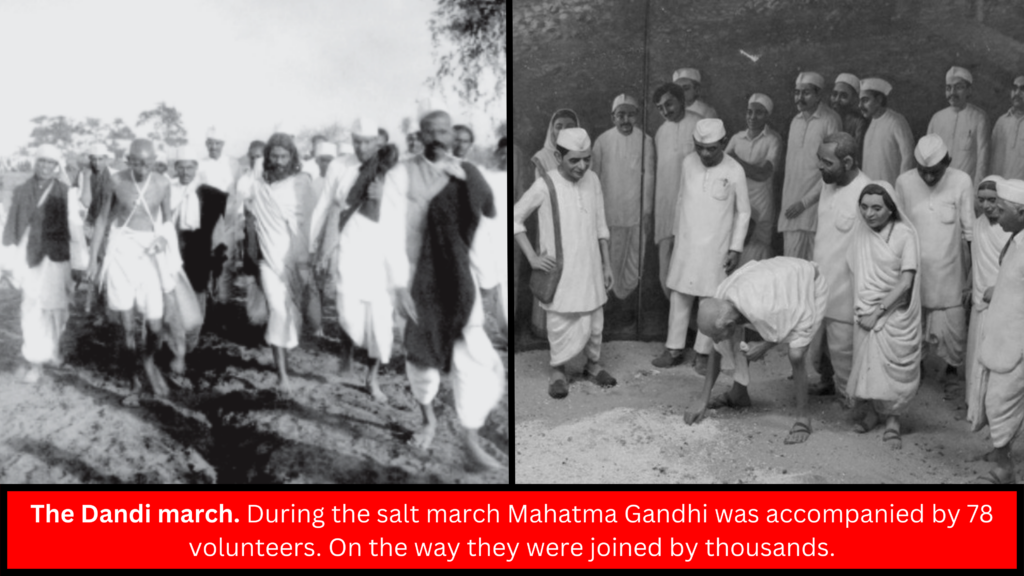

The Salt March : Nationalism in India

- Gandhiji began the salt march from his Sabarmati ashram to the coastal town of Dandi.

- He was accompanied by 78 volunteers. The distance was approximately 240 miles.

- To reach their destination, Gandhiji and his volunteers walked for 24 days, covering 10 miles per day.

Many people gathered at a - During Gandhi’s march, many people came over to join him. They listened to what he had to say about Swaraj and the importance of fighting for independence peacefully.

- Gandhiji broke the salt law on April 6, manufacturing salt by boiling seawater.

The Civil Disobedience Movement : Nationalism in India

- The civil disobedience began at the conclusion of the Salt March. Along with refusing to cooperate with the British, locals were also asked to violate colonial laws.

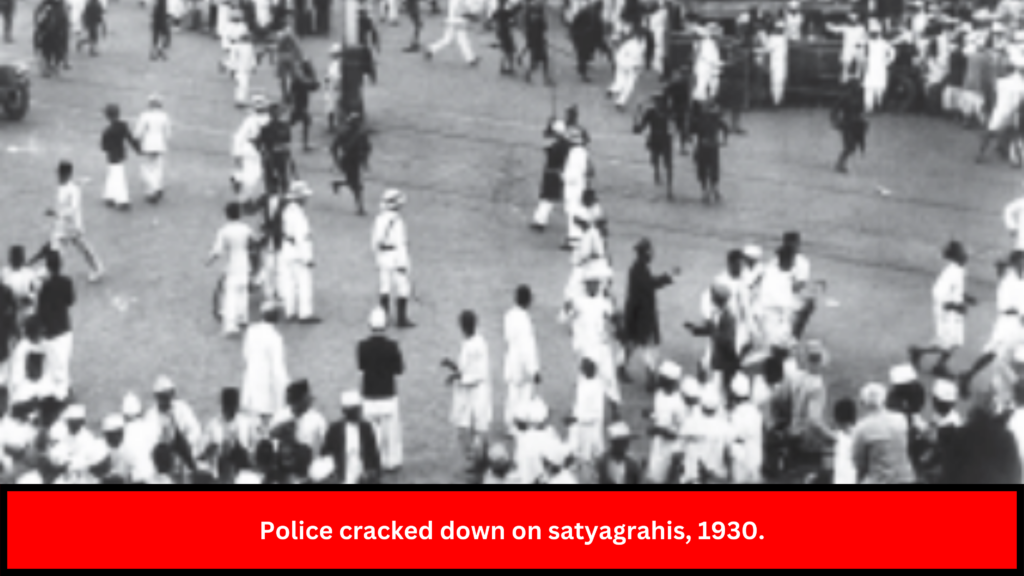

In many parts of India, people broke the salt law and protested outside salt factories. - In various places of India, people defied the salt law, protested outside salt plants, refused to pay revenue and chowkidar taxes, and resigned from their positions. People picketed liquor stores and boycott foreign goods, and they entered restricted areas in forests to obtain wood and pasture animals.

- As a result of the uprising, government officials began to arrest Congress leaders. When Abdul Ghaffar Khan was arrested, there were protests in Peshawar against police shootings, and many people were killed.

- When Mahatma Gandhi was arrested, police stations, municipal buildings, and train stations were all attacked. Because it was unable to control the people, the government took more aggressive measures.

- As violence escalated, Mahatma Gandhi called a halt to the movement by signing the Irwin Pact on March 5, 1931. Gandhiji promised to attend the Round Table Conference in London, according to the agreement.

- However, after attending the Conference, he was dissatisfied with the outcome of the negotiations. When he returned to India, he discovered that the government had declared Congress illegal, that prominent leaders were imprisoned, and that meetings and gatherings were prohibited.

- Gandhiji relaunched the Civil Disobedience Movement, which lasted over a year before losing steam by 1934.

3.2 How Participants saw the Movement : Nationalism in India

Rich Peasant Community : Nationalism in India

- Swaraj meant a fight against the rising revenue rates for the wealthier peasants.

- This fueled resentment toward the government, which refused to reduce the revenue demand.

- When Mahatma Gandhi launched the movement, the rich peasant community reacted negatively.

- The rich peasant community actively participated in the fight when Mahatma Gandhi launched the movement.

- As a result, when the movement was relaunched, the wealthy peasants refused to take part.

Poor Peasant Community: Nationalism in India

Poor peasants desired a reduction in revenue demands as well as the remittance of unpaid rents to landlords and rich peasants. The poor peasant demands were not voiced for fear of disappointing the rich peasants who financially supported the congress party.

Business-class Community : Nationalism in India

- People from the business class wanted to expand their operations in India and abroad.

- However, the Company’s control over import duties and trade restrictions hampered their growth.

- Industrialists formed the Indian Industrial and Commercial Congress in 1920 and the Federation of the Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industries (FICCI) in 1927 to oppose colonial policies.

- The business elite saw the Civil Disobedience movement as a watershed moment in which their trade monopoly would be challenged.

- When the movement was halted, they became concerned about military activities, fearing that trade restrictions would be tightened and their businesses would suffer significant losses.

Industrial Working Class : Nationalism in India

Except in the Nagpur region, industrial working-class people did not enrol in huge numbers. As they were afraid, the Congress party did not incorporate their demands such as poor salaries and proper working conditions.

Women : Nationalism in India

Women joined the campaign because they saw it as their holy duty to the nation.

- Many women came out of their homes to listen to Gandhiji during the salt march.

- Women from wealthy peasant and upper caste households made up the majority of those who took part.

- They boycotted foreign goods, protested, and picketed liquor stores.

- The Congress party did not encourage women’s participation since they believed women were supposed to look after household responsibilities and family. Despite their efforts, the women were not offered positions in the party.

3.3 The Limits of Civil Disobedience

The Untouchables : Nationalism in India

The ‘untouchables’ were a sector of society that was discriminated against by the rest of society.

- Inclusion of their interests and demands by the Congress party was not deemed helpful because it would have irritated the upper-class members.

- But Gandhiji saw everyone as equal and stated that every member of society is significant and that every work done contributes to the larger good of humanity.

- He desired equal involvement in the movement for the Dalits, as they became known.

- The Dalits, on the other hand, desired a political advantage by being able to vote separately in the electorate, which would select solely Dalit members for legislative councils.

- They hoped that political status would give them advantages in lawmaking and give them a say in decision making.

- Poona Pact was signed in September 1932, according to which the Dalits would be given reserved seats in the legislative councils.

Muslims : Nationalism in India

- Muslims’ reaction to the Civil Disobedience Movement was unexpected.

Members of the Congress party were more drawn toward religious organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha. - The Muslim League and the Congress party attempted to reconcile their differences.

- All those hopes, however, were dashed when M.R. Jaykar of the Hindu Mahasabha openly opposed the reunion at the All Parties Conference in 1928.

- Muslims feared that because they were minorities, their religion would dwindle under Hindu dominance, and their interests would be overlooked.

4. The Sense of Collective Belonging : Nationalism in India

Opposing colonial rule required a concerted effort from all communities, each with their own reasons.

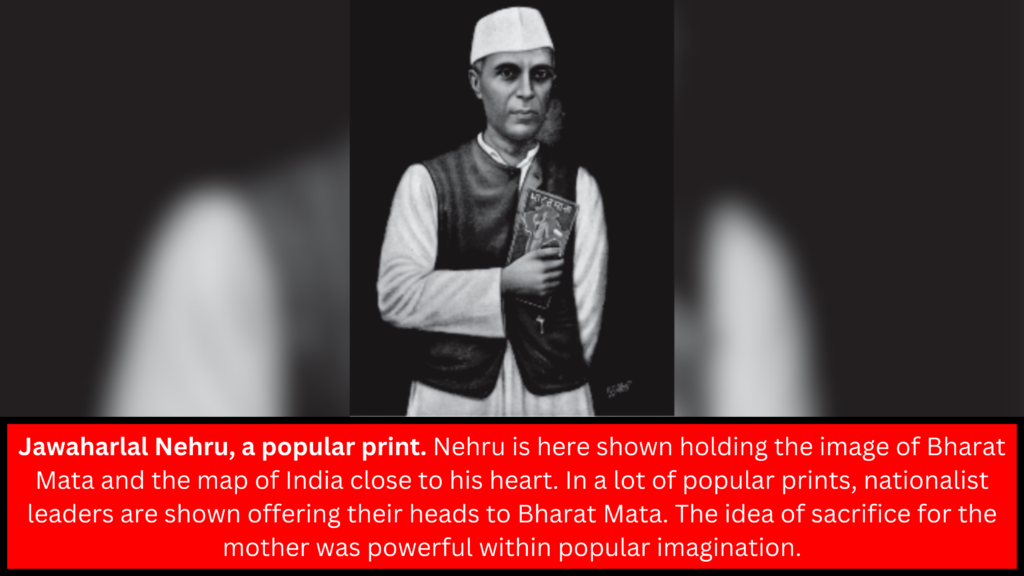

- The concept of a unified nation arose in the minds of great leaders and gradually took root in the minds of the people.

- India, like many other countries, came to be represented as an image: Bharat Mata. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay was the first to bring it up.

- Vande Mataram was written in the 1870s by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. The song was popular during the Swadeshi movement and the fight for independence.

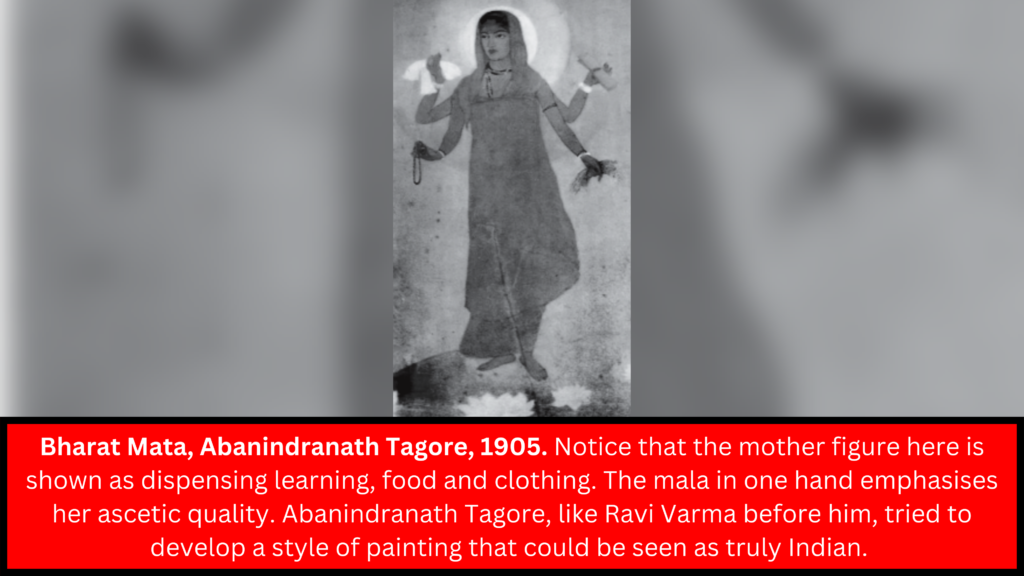

- Abanindranath Tagore painted a portrait of Bharat Mata that portrayed calm, divinity, and spirituality.

Collecting and restoring old stories and songs was seen as a way to connect with a country’s culture, leading to a sense of oneness.

- Rabindranath Tagore amassed a collection of ballads, poems, and myths.

- The Folklore of Southern India by Natesa Sastri is a four-volume compilation of Tamil folk stories.

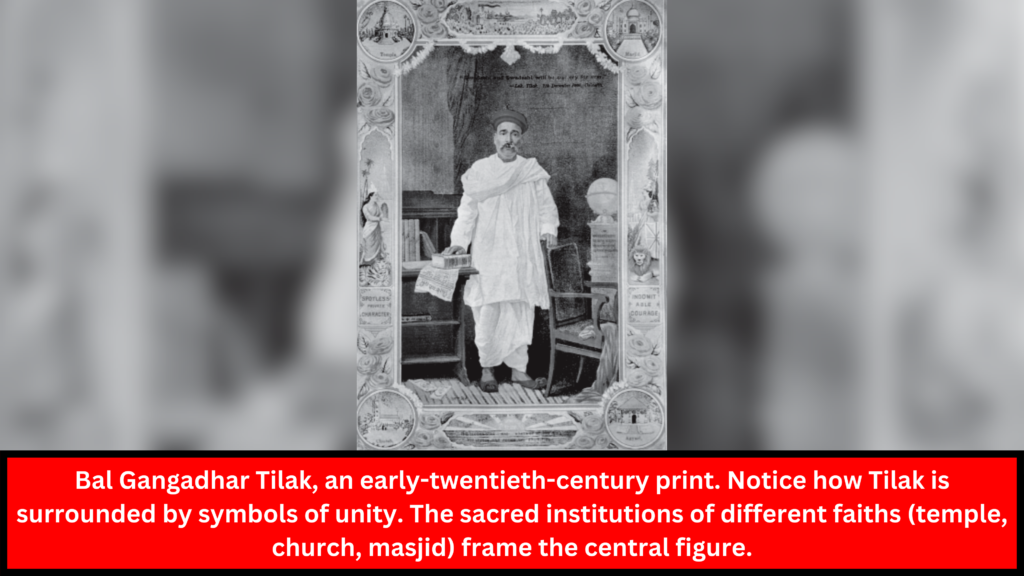

Symbols and icons were also used to bring people together.

- A tricolour flag (red, green, and yellow) was designed in Bengal. It was decorated with eight lotuses and a crescent moon.

- The lotuses represented the eight provinces under British rule, while the moon represented Hindus and Muslims.

- Gandhiji created a tricolour flag (red, white, and green) with a spinning wheel in the centre in 1921. The wheel symbolised its reliance on itself for progress and wealth.

- Redefining history and taking pride in its rich culture and traditions became associated with nationalism.

- People proposed that India was a country of brave and great rulers prior to colonialism.

- Under their leadership, India excelled in scientific, ayurvedic, philosophical, artistic, literary, and other fields.

- Bringing to people’s attention what colonisation had done to their wonderful homeland created animosity for British control and developed in people’s minds a collective will to fight for their motherland.

5. Conclusion : Nationalism in India

The movement experienced high points of Congress activity and nationalist unity, but also phases of disunity and inner conflict, creating a nation with many voices wanting freedom from colonial rule.

Check out the important Dates of History Post on etutorguru.in

6. Download PDF Notes : Nationalism in India

7. Download MindMap : Nationalism in India

Coming Soon

8. NCERT Solutions : Nationalism in India

Exercise Page No. 50

Write in brief.

1. Explain

a. Why the growth of nationalism in the colonies is linked to an anti-colonial movement?

Answer:

- People began discovering their unity in the process of their struggle with colonialism.

- The sense of being oppressed under colonialism provided a shared bond that tied many different groups together.

- But each class and group felt the effects of colonialism differently.

- The Congress under Mahatma Gandhi tried to forge these groups together within one movement.

- But unity did not emerge without conflict.

b. How the First World War helped in the growth of the National Movement in India?

Answer:

War changed the political and economic landscape.

- The war resulted in a massive surge in defence spending, which was supported by war loans and higher taxes.

- Customs taxes were raised, and an income tax was implemented.

- Villagers were outraged at forced recruitment.

- Crops failed, resulting in a severe food scarcity.

- Famines and diseases killed 12 to 13 million people.

c. Why were Indians outraged by the Rowlatt Act?

Answer:

- The war resulted in a massive surge in defence spending, which was supported by war loans and higher taxes.

- Customs duties were hiked, and an income tax was imposed.

- Villages were horrified by the forced recruiting.

- Crops failed, leading in serious food scarcity.

- Famines and illnesses killed 12 to 13 million people.

d. Why Gandhiji decided to withdraw the Non-Cooperation Movement?

Answer:

The war caused a large increase in defence spending, which was financed by war loans and higher taxes. Customs taxes were increased, and an income tax was instituted.

The forced recruitment shocked the villages.

Crops failed, leading in serious food scarcity.

Famines and illnesses claimed the lives of 12 to 13 million people.

2. What is meant by the idea of Satyagraha?

Answer:

- Satyagraha emphasised the importance of truth and the necessity to seek it.

- It implied that if the cause was just and the struggle was for justice, then physical force was not required to resist the oppressor.

- A satyagrahi could win the conflict via nonviolence rather than seeking vengeance or being confrontational.

- Ultimately, the truth would triumph as a result of this conflict.

- Mahatma Gandhi believed that this nonviolent dharma could unify all Indians.

3. Write a newspaper report on

a) The Jallianwala Bagh massacre

Answer:

- A crowd had assembled in Jallianwalla Bagh’s walled ground.

- Several people came to oppose the government’s new harsh tactics.

- Many villagers were ignorant of the martial law that had been established because they were from outside the city.

- Dyer stormed the scene, barricaded the exits, and opened fire on the throng, killing hundreds.

- Many were terrified and awestruck by the incident.

b) The Simon Commission

Answer:

- The Simon Commission was met with the phrase “Go back, Simon” when it landed in India in 1928.

- The demonstrations were attended by representatives from all political parties, including the Congress and the Muslim League.

- In an attempt to sway them, Viceroy Lord Irwin announced in October 1929 a vague offer of ‘dominion status’ for India in the future and a Round Table Conference to consider a future constitution.

- This did not satisfy the leaders of Congress.

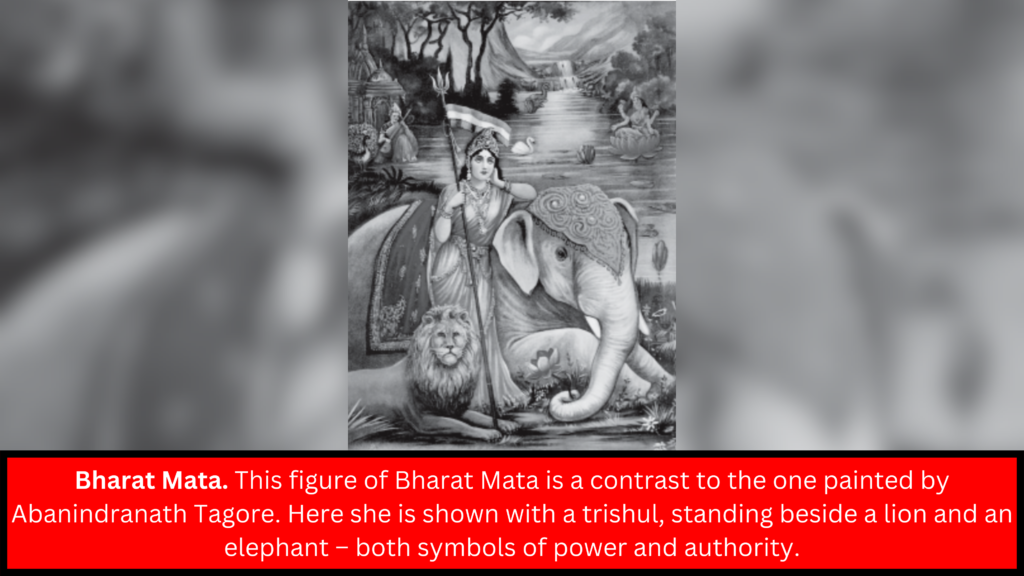

4. Compare the images of Bharat Mata in this chapter with the image of Germania in Chapter 1.

Answer:

Germania:

- Symbol of Germany

- The image was painted by Philip Veit in 1848.

- Carrying a sword in one hand and flag in another hand Germania is wearing a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak stands for heroism.

Bharat Mata:

- Symbol of India

- Abanindranath Tagore painted it in in 1905.

- Bharat with a Trishul beside a lion and elephant, symbols of power and authority,

Discuss

1. List all the different social groups which joined the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1921. Then choose any three and write about their hopes and struggles to show why

they joined the movement.

Answer:

The following is a list of the various social groups that joined the Non-Cooperation Movement, as well as their struggles.

Middle-class Participation in Cities

- Thousands of students left government-controlled schools and colleges, headmasters and teachers resigned, and lawyers gave up their legal practices.

- The council elections were boycotted in most provinces, except Madras, where the Justice Party, the party of the non-Brahmans, felt that entering the council was one way of gaining some power – something that usually only Brahmans had access to.

- The effects of non-cooperation on the economic front were more dramatic.

- The import of foreign cloth halved between 1921 and 1922, its value dropping from Rs 102 crore to Rs 57 crore.

- In many places, merchants and traders refused to trade in foreign goods or finance foreign trade.

- As the boycott movement spread and people began discarding imported clothes and wearing only Indian ones, the production of Indian textile mills and handlooms increased.

- But this movement in the cities gradually slowed down for various reasons.

Khadi cloth was often more expensive than mass-produced mill cloth, and poor people could not afford to buy it.

Similarly, the boycott of British institutions posed a problem. For the movement to be successful, alternative Indian institutions had to be set up so that they could be used in place of the British ones. These were slow to come up. So students and teachers began trickling back to government schools, and lawyers joined back work in courts.

Peasants and Tribals

- Peasants in Awadh were headed by Baba Ramchandra, a sanyasi who had previously worked as an indentured labourer in Fiji.

- There was a movement there against talukdars and landowners who sought exorbitant rents and other cesses from peasants.

- Peasants were forced to to beg and work on landlords’ farms for free.

- They had no security of tenure as tenants, as they were frequently evicted, leaving them with no right to the rented land.

- The peasant movement called for revenue reductions, the abolition of begar, and a social boycott of unjust landlords.

- Panchayats organised ‘nai-dhobi bandhs’ in numerous localities to deprive landlords of the services of barbers and washermen.

- Tribal peasants perceived Mahatma Gandhi’s message and the concept of swaraj in a different way.

- The colonial authority had blocked extensive forest sections in other forest regions, forbidding residents from entering the trees to graze their livestock or collect fuelwood and fruits.

- The hill people were outraged by this.

- Not only were their livelihoods jeopardised, but they also believed that their traditional rights were being violated.

- The hill people revolted when the government began requiring them to donate begar for road construction.

Workers in the Plantations

- Workers have their own interpretations of Mahatma Gandhi and the concept of Swaraj.

- For Assamese plantation labourers, freedom meant the ability to travel freely in and out of the constricted space in which they were enclosed, as well as the ability to maintain a connection with the community from which they had come.

- Plantation labourers were not permitted to leave the tea gardens without permission under the Inland Emigration Act of 1859, and such permission was rarely granted.

- Many of the employees disobeyed the government, abandoned the plantations, and returned home after learning about the Non-Cooperation Movement.

- They expected Gandhi Raj to arrive and offer everyone land in their own villages.

They, on the other hand, never arrived at their destination. They were apprehended by authorities and brutally assaulted while stranded on the road due to a railway and steamer strike.

2. Discuss the Salt March to make clear why it was an effective symbol of resistance against colonialism.

Answer:

- Mahatma Gandhi discovered in salt a potent symbol capable of uniting the people.

- On January 31, 1930, he sent Viceroy Irwin a letter with eleven demands.

- Some were of wide interest, while others were special demands of certain strata, ranging from industrialists to peasants.

- The objective was to broaden the demands so that all classes within Indian society could connect with them and join forces in a single campaign.

- The most stirring demand was to repeal the salt charge.

- Salt was something that was consumed by both the rich and the poor, and it was one of the most important food items.

- The most onerous face of British authority, as revealed by Mahatma Gandhi, was the salt tax and the government monopoly over its production.

- Mahatma Gandhi began his historic salt march with the help of 78 of his loyal volunteers.

- From Gandhiji’s ashram at Sabarmati to the Gujarati seaside town of Dandi, the march covered nearly 240 km.

- The volunteers walked for 24 days, covering approximately 10 miles every day.

People flocked to hear Mahatma Gandhi wherever he went, and he explained what he meant by Swaraj and exhorted them to defy the British peacefully. - On April 6, he arrived at Dandi and ceremonially broke the law by boiling seawater to make salt.

- Hundreds of people across the country disobeyed the salt ban by producing salt and protesting in front of government salt facilities.

As the movement gained traction, international clothing was boycotted, and liquor stores were picketed. Peasants refused to pay revenue and chowkidar taxes, village administrators resigned, and in several places, there was a general strike.

3. Imagine you are a woman participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement. Explain what the experience meant to your life.

Answer:

Students are encouraged to take on the roles of women and share their experiences.

4. Why did political leaders differ sharply over the question of separate electorates?

Answer:

- In the second Round Table Conference, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who organised the Dalits into the Depressed Classes Association in 1930, clashed with Mahatma

- Gandhi by demanding separate electorates for Dalits.

- When the British government agreed to Ambedkar’s demand, Gandhiji began a death fast.

- Separate electorates for Dalits, he argued, would impede the pace of their assimilation into society.

- Ambedkar eventually agreed to Gandhiji’s position, resulting in the Poona Accord of September 1932.

Muhammed Ali Jinnah was willing to abandon his demand for separate electorates in exchange for reserved seats in the Central Assembly and representation in proportion to population in Muslim-dominated provinces (Bengal and Punjab). Talks over representation continued, but all chance of resolving the matter at the All Parties Conference in 1928 vanished when M.R. Jayakar of the Hindu Mahasabha firmly opposed any attempts at compromise.